My grandfather was the son of a 10th generation Belgian coal miner. Ten that we know of, it could be 15 or 20 as men have been mining in the low country of Belgium since coal was discovered there at the end of the 12th century.

The graphic below reflects the Belgian tradition that the existence and use of coal was revealed to a poor wheelwright named Houillos by an angel disguised as an old man.

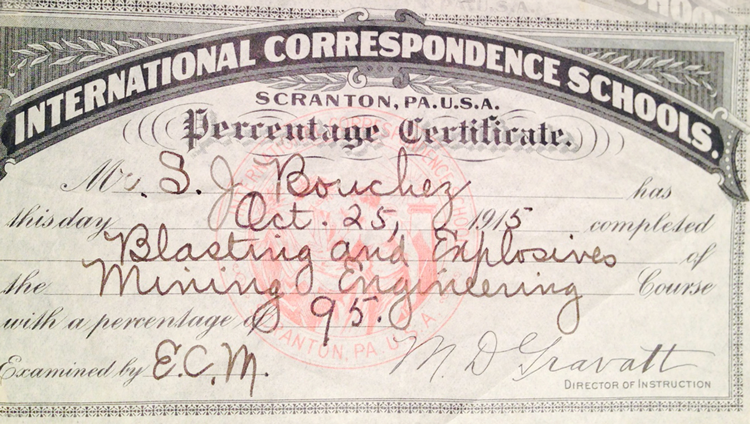

A stack of percentage certificates for correspondence courses in mining engineering among my grandfather’s personal effects, indicate that if he did, it was not without a plan.

There are 38 certificates for a range of subjects, from arithmetic, formulas, geometry and trigonometry to geology of coal, timbering, mechanics, and more.

This one is my favorite.

There is however, no diploma. I presume he finished but unfortunately there is no way to find out. (I tried.)

International Correspondence Schools, Scranton, Pennsylvania, founded in 1891, stressed education as a path to upward mobility and promotion rather than the moral uplift favored by early educational reformers. Courses were constructed to provide students with knowledge they could immediately apply to the job. (Source: University of Scranton)

Laborers such as my grandfather looked to correspondence courses to lift out them of the working class, according to “Education for Success: The International Correspondence Schools of Scranton, Pennsylvania.” a paper written by James Watkins that appeared in the Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography in 1996.

The article opens with this quote:

The dignity of labor is a fiction. To the intelligent and the educated belong the dignity. To labor remains the burden. — J.C. Bayless, American Institute of Mining, 1885

Did it work? The ICS Mining Engineering course of study included units on Mine Surveying and Mapping and Geometrical Drawing, two certificates that are missing. Yet the occupation listed on my grandfather’s WWI draft card, dated 21 September, 1918, is surveyor. If he used them to prove his expertise to his employer, they may not have made it back into the file.

At some point after 1918, my grandfather relocated to St. Louis and on the 4th of November, 1919, he enlisted in the Navy.

His ICS education gave him an edge there as well. He served as a Machinist’s Mate in San Diego, California for a year and then was sent to Aviation Machinist’s school at Great Lakes Naval Base in Illinois for a year, then back to San Diego until he was honorably discharged on the 3rd of November, 1922. Classification: Aviation Machinist’s Mate, Second Class.

Two years later, he met my grandmother at her brother’s wedding and married her in 1925. My father was born in 1927, and the first of two sisters followed in 1928.

The arrival of the Depression in 1929 brought new struggles but the knowledge and expertise my grandfather had acquired through his dogged efforts to acquire education enabled him to remain employed. According to the 1930 U.S. census, he and his family were living in Detroit. His occupation was noted as “Aircraft Motor Tester.”

The aircraft was the Ford Tri-Motor, the first all metal aircraft and the motor Grampa was testing was among the most innovative of its time. I know this because there is a Ford Tri-Motor in the Henry Ford museum in Dearborn and my dad would point it out to me each time we visited.

Correspondence school and aviation trade school had provided my grandfather a modicum of security by lifting him out of labor. He was determined to make sure his children would never need to return to it.

My Dad has often spoken of the lengths that Grampa went to to reinforce the indignities of demanding physical labor — getting him the dirtiest job possible dipping engines at Hercules, then working with local recruiters to “facilitate” his enlistment in the US Army.

After the service, Dad enrolled in college, which was paid for on the GI Bill. He earned a degree in engineering and later, his designation as a Professional Engineer. I think he was prouder of the PE than his degree, and given that examination process (and the fact it was done by slide rule), it’s easy to understand why.

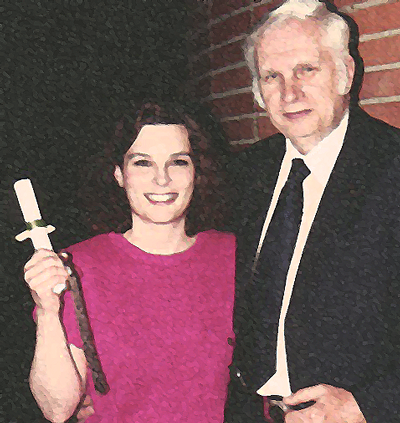

Like his father, ours was determined that we (my sister and I) receive an education. He started putting money away for us for this purpose from the day we were born. Granted, it took me a while to get done, but I’ll always remember how proud and relieved he was when I finally did. (Me too.)

Like his father, ours was determined that we (my sister and I) receive an education. He started putting money away for us for this purpose from the day we were born. Granted, it took me a while to get done, but I’ll always remember how proud and relieved he was when I finally did. (Me too.)

Education enabled my grandfather to break a centuries long pattern and chart a new course for himself; inculcating his children with its imperative created an enduring value that ensured education would remain a priority and benefit his decendants for generations to come.